Isaiah 9:2-7

Ps. 96

Titus 2:11-14

Luke 2:1-20

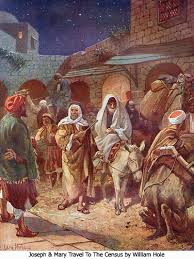

Christmas Eve is a time to tell old stories --- to thrill at the hearing of the things we know and have heard many times, to recreate in our imagination the trip from Nazareth to Bethlehem, the last-minute accommodations in the stable, the ordinary birth as miraculous as all ordinary births, the angels, the shepherds, the wise men from the east. In my mind, no matter what

translation is read, the pictures are the same ones I formed as a child -- the dark, cold night, the brightness of the star, the shepherds on a hill illuminated by the glow of the angels, the little barn full of straw and animals.

translation is read, the pictures are the same ones I formed as a child -- the dark, cold night, the brightness of the star, the shepherds on a hill illuminated by the glow of the angels, the little barn full of straw and animals. The Gospel of Luke is precise in what is described; it seems almost like fact. “In those days a decree went out from Caesar Augustus that all the world should be enrolled. This was the first enrollment, when Quirinius was governor of Syria….” Are we not reading a history text here?

Well, yes and no. Scholars tell us there is “no evidence of one census under Augustus that covered the whole Empire, nor of a …requirement that people be registered in their own cities….” But Caesar Augustus was the emperor, and we do know that the empire wanted its taxes, and to get an accurate accounting for tax purposes, these people had to be counted. If we were hearing this story 2000 years ago, we’d know that that part of the story is true.

I also love this part: “In that region there were shepherds living in the fields, keeping watch over their flock by night.” We know what they angel says – aren’t we amazed that this great good news comes first to the poorest of the poor, the hard-working shepherds who never get a day off?

“And suddenly there was with the angel a multitude of the heavenly host …” “The heavenly host.” If we were hearing this in its original language, we would have heard it like this: “And suddenly there was with the angel a multitude of the heavenly army …” Just what kind of a history are we reading here? This isn’t just a sweet, romantic story; it’s a story told with power – a story of how God acts in history, on behalf of poor people like shepherds, a story of how God takes on big, oppressive political powers like the Roman Empire, how God’s army swoops down among us bringing real peace, real good tidings, real good news for all people – not just the people who would benefit from those taxes levied on the people being counted in that census.

The Christian story is rooted in the life of the body. Christmas is a celebration of the Incarnation of Jesus as God made human, and so this story of God’s interaction with us is inseparable from all of the joyful, painful, and even political experiences of human life.

The truth of this story is found in the ordinary and extraordinary birth of a baby boy, and in these miraculous appearances of angels and shepherds and wise men from the East. No matter how or how often we tell it, the truth lies in trusting the body: For God has trusted the cosmic disclosure of God’s self to a mere human form; with the birth of this babe, the human condition IS God’s condition. And so if God has “trusted the body” to that extent, so may we – trust in the body of the faithful that the stories we continue to tell to each other about God are true. Tonight we tell the true story of the Coming Day of Peace. We tell the true story that Jesus, true God and true man is born. We who are fully aware of what it means to be human, in all or our weakness and vulnerability, hear this story of ultimate vulnerability and weakness in the birth of the Savior, this little babe, who is Christ the Lord.

Christmas 2-B

January 4, 2009

Isaiah 61:10-62:3

Psalm 84:1-8

Ephesians 1:3-6, 15-19a

Luke 2:41-52

Did you read the story in yesterday’s Enterprise? “New survey reveals changes in churches.” It was on page 15, the first page of the “Lifestyle” section.

Just about all of us could read that article and say, hah. So what’s the new news here? We know churches have been changing dramatically over our lifetimes.

How many of you were raised in a different church than this one – than St. Paul’s Church? How many of you were raised in a church different from the Episcopal Church? Or, were you raised in the Anglican Communion but in another country? Were you raised learning the Lord’s Prayer in a language other than English? How many of you, when you were 10 years old, knew that women could be ministers?

That article in yesterday’s Enterprise talked about some of those changes. Religion, one of those things we thought were unchanging, seems to have thrown all the pieces on the game board up in the air, and I don’t think we know exactly where they will be coming down – or if they will ever come down again to anything resembling the stability and security we think “religion” ought to have.

You know, we were wrong in the ‘60s when we thought that it was just the young people, or the Jesus freaks, drifting away from church – that the cultural changes would shake out and when all those hippies and evangelicals would “get it out of their system” and come back to church once they got married and had children. I think any of us who moved from one culture to another, from a different continent or island to this great, huge United States would know how wrong that idea is. Once a culture changes, it changes; in many profound ways, none of us can go home again. Believe me: no matter what kind of church – or no church – you grew up in, no matter where in the world, or in the U.S., you grew up, this church here today is very different from the church or 30, or 20, or even 10 years ago. Check out the article during coffee hour. As a former teacher of mine, who in her young adulthood fled Nazi Germany, said, “Change is here to stay.” Imagine, then, what impact the visit of the young Jesus to the Temple had on … his parents? On the Temple leaders and teachers? On the people who first heard this story, this biographical snippet from the young life of the man people had come to know as Teacher, as Leader, as the Crucified one, as the Risen Lord?

On every score, what Jesus does in this story upsets the status quo. This little story, coming at the end of Chapter 2 in the Gospel of Luke, is the last of the “infancy narratives” –the last bit of evidence that Luke puts out that this Jesus, this baby boy born in a stable to a poor mother, whose birth was announced by an army of angels to poor shepherds in the fields that he would be the true king, the true bringer of peace, the true one to ensure the

prosperity of humankind, was the real thing. His birth heralded the new age, the new world order, the end of the empire of violence and military might and over-taxed exploitation.

prosperity of humankind, was the real thing. His birth heralded the new age, the new world order, the end of the empire of violence and military might and over-taxed exploitation.This little story is also the first time we read of Jesus’ public ministry. He is a teacher, a proclaimer of the true word of God. Even at age 12 – he is the one who knows that he is to do what God would have him do – that he is both a profound and complete break with the past as well as the fulfillment of what God has been trying to get across to humanity since the beginning of time. When he leaves the Temple with his parents, he will not return until a few days before his death on the cross, when he denounces the Temple leaders for their corrupt rule and the cruel taxes the poor cannot pay.

We might want religion to be something comfortable and stable and never-changing. We might want choirs of angels to lull us to sleep. But a fierce, hot wind is blowing, like the one that blew Jesus from Nazareth to Jerusalem thousands of years ago. The wind is that Spirit of God, restless and powerful, blowing in this new world, forcing us to pay attention to what God is calling us to be and to do now, here, in this place, with these people. “Did you not know that I must be in my Father’s house?” Jesus asked his bewildered parents. Don’t we sympathize with them? How can things change so quickly?

For the people who first read the Gospel of Luke, that change was long overdue. At the beginning of Chapter 2, this boy was born under the thumb of the brutal Roman Empire, yet heralded by an army mightier than all their legions. Now, here, at the end of the same chapter, he is wise enough to tell the teachers in the Temple what the ancient texts mean. At the end of these two chapters, in which Luke tells us just where this Jesus came from, it’s like he is saying to us, hold on to your seats. The best is yet to come. Change is here to stay.

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)